A Primer On Succession Planning

Printer Friendly Version

I. Impediments to Successful Transitions

A. External Forces. Family owned and other closely held businesses rarely survive past the first generation of owners due, in part, to their relatively limited resources and restricted marketability of ownership shares, when compared to publicly traded companies, leaving them more vulnerable to external forces. Among the outside factors that tend to cause family owned and other closely held businesses to fail over time are: (i) changes in the consumer market due to age and other demographics, (ii) technological changes and advances, (iii) competition and (iv) the incurrence of substantial transfer taxes.

B. Internal Forces. Among the internal factors that impede successful transition of even thriving family owned and other closely held businesses are: (i) lack of successor leadership, (ii) lack of successor talent and (iii) complacency of leadership and/or the workforce.

C. Acquisition Load. In the case of a sale of the business (whether to family members or outsiders), the favorable economics of running the business may substantially change due to the costs associated with the acquisition of the business, particularly ongoing debt service payments on the acquisition price.

D. Generational Division. Even if the business is transitioned “free” to the next generation of family members and the business continues to operate at historical levels, the generational split of operating profits, usually involving multiple heirs at each generational level, may eventually dilute the favorable economics of running the business over time and may account for one of the main reasons why family businesses seldom survive after the first generation and rarely make it into the third generation.

E. Succession Planning or Reactive Succession. A business succession (or cessation) can be planned for in advance or can occur as a non-planned reaction to a succession event (usually to the key owner, such as death, disability or retirement).

II. Lack of Planning for a Business Succession

A. Impediments to a Planned Succession. While many would imagine that developing the managerial and operational transition of a valuable business would be a normal and ongoing component of business procedures, being planned well in advance, it is all too common for succession planning to be neglected and left unplanned. While there may be many causes for this lack of planning, in this author’s view, most or all of these causes can be directly or indirectly attributed to HUMAN NATURE.

B. Human Nature.

1. Disclaimer. One could write vast volumes on the topic of human nature and its possible impact on business operations and succession implementation. Everything said could be absolutely true at some level and totally unfounded at another due to the intricacies and complexities associated with human behaviors that defy quantification and objectivity to any degree of predictability or certainty. Only a fool would attempt to provide any type of significant guidance in this area. So, here goes the fool. However, before continuing, the reader is forewarned that all or most of the following (i) reflects only the author’s views, (ii) are, in large part, simplified and intentional generalizations for illustrative and discussion purposes, (iii) are unproven (and unprovable) concepts and (iv) cannot be entirely relied upon for any purpose. That being said, the author feels that there may be some value in pursuing this line of thought in an endeavor to understand the human motivational constraints and impediments that underlie and often confound the succession planning process, as brief and rudimentary as the following analysis may be.

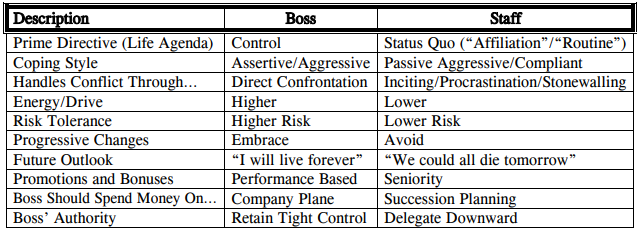

2. Boss/Staff Motivations and Attributes. Often non-owner employees wonder why so little focus is placed upon succession planning in the respective companies for which they work. Over the years, many of these valuable and loyal employees have expressed to this author their concerns about the impact their boss’ untimely death or retirement would have on the business, their jobs and the jobs of their fellow employees, as well as the welfare of the boss’ family members to whom they have often grown close. How can the respective owner/bosses be so indifferent to this important subject? In this author’s view, the answer is very simple when you take into account human nature. The chart below explores the possible “tensions” between the differing motivations and values often indicative of the owner (boss), on the one hand, and the non-owner employees (staff), on the other.

Tensions Created by Differing Motivations/Values of Bosses Compared to Staff

On the other hand, changing perspectives, it could equally be logical and reasonable for another person to feel that it is prudent to spend significant time and money on a succession plan that may ensure continuation of the business into the next generation of management, particularly when such person’s primary focus in life is maintaining their affiliation with the company and its people and/or preserving the status quo or routine of their work life, they lack the assertiveness, risk tolerance and/or drive to operate their own business and they are generally dependent on the survival of someone else’s business for their livelihood (the “staff”).While the foregoing chart is obviously an oversimplification and generalization of the motivations and driving forces of bosses as compared to staff personnel (see above disclaimer), one can see that one’s concept of what is important, and, thus, should be pursued, changes based on the differing perspectives of the person making the determination. Thus, it could be totally logical and reasonable for one person to feel that there is not much need or importance in spending significant time and money on a succession plan that would entail, among other things, the delegation of management control and/or the redirection of business value or cash flow to others, when such person’s primary focus in life is obtaining and maintaining control and financial resources, they believe they can overcome any challenge with or without planning and they expect to live and work “forever” (the “boss”).

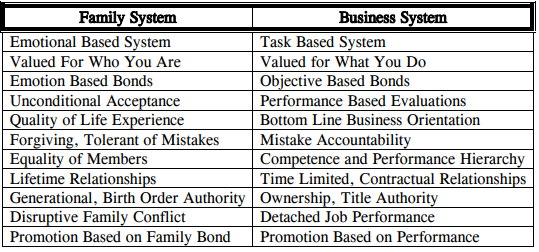

3. Interaction of Business System/Family System Dynamics. The successful transfer of a family business intended to be passed on to younger generational family members is often negatively impacted by the often oppositional interaction of the dynamics associated with a business system of values versus those of a family system of values. Thus, choosing a management successor from the pool of family members often runs contrary to the familial roles played by the various family members. That is, the family member successor that might be chosen under a familial value system may often run counter to the one chosen pursuant to a set of business system principles. Some of these oppositional values or principles include:

Tensions Created by Differing Family System/Business System Dynamics

C. Uncertainty of Efficacy of Various Succession Planning Strategies.

The uncertainties, complexities and economic risks associated with various succession planning strategies, most of which are tax driven, also work to weaken the resolve of business owners to implement significant succession activities in advance, even when such business owners might otherwise be open to such planning. For example, self-canceling installments notes, private annuities, grantor retained annuity trusts (“GRATs”) and intentionally defective grantor trusts (“IDGTs”) can provide substantial economic and tax benefits, or such devices can bring considerable economic and tax burdens, depending on such variable conditions as, among other things, actual life span versus life expectancy, available liquidity from the business to fund payments and future appreciation or depreciation of the business. Even solidifying the successor and purchase price conditions in a binding legal contract well in advance can cause many undesirable effects due to possible changing conditions between the time of contract execution and the time of the succession event giving rise to the contract’s implementation. Therefore, very careful attention must be given to any advance succession planning technique.

III. Planning a Business Succession

A. Identifying Successor Control and/or Successor Ownership (the “Who”). Perhaps the first step in succession planning is identifying the persons who will step into successor control and/or successor ownership. Often successor control will be tied to successor ownership; however, it is sometimes advisable to separate successor control from successor ownership in certain circumstances. One example would be where the business owner wishes to transfer ownership of the family business to his family, but no family member has the ability or the desire to run the business. In such case, management of the business might be entrusted to existing non-family key employees pursuant to appropriate employment contracts. Another example might be where the family business will be passed on to more than one family member, but less than all of such family members will be active in the business. In such case, control may be placed in the active family member or members, while ownership is transferred to all applicable family members, active and inactive.

Or, where there is no competent inside successor and/or a lack of commitment to the business by the younger generation, identification of potential third party purchasers of the business is probably in order.

B. Manner of Succession (the “How”). Once the successor is identified, whether it be family members, current key employees, or third party purchasers, the manner of succession should be planned.

1. Succession to Family Members. If the succession is to family members, the owner must determine whether the transfer will be “free” or by “sale”. Often, pre-death successions are structured as “sales” in order to provide the owner (or owner’s spouse) with continued cash flow.

2. Succession to Other Parties. If the succession is to non-family members, the succession will usually be in the form of a sale transaction.

C. Control Strategies. As discussed previously, it may be desirable to separate control of the business from ownership of the business. If the owners (senior generation) are willing to currently give up partial ownership of the business (usually due to transfer tax considerations), but not control, several entity structuring techniques can accomplish this. For corporations, voting and non-voting shares can be created (without impacting any S corporation election of the corporation), with the senior generation retaining the voting shares. For limited liability companies, membership interests can be separated into voting interests and non-voting interests. Interests in limited partnerships are already separated into (managing) general partner interests and (non-managing) limited partner interests.

Other control retention techniques may include the implementation of (i) super-majority voting requirements, (ii) guidelines for officer, director and/or manager selections and (iii) voting agreements and voting trusts.

D. Multiple Entity Planning. Maintaining multiple entities can address various operational, estate and succession planning objectives. From the operational side, multiple entity structuring can provide significant protection against creditors. If structured properly, assets of one entity are generally shielded from the liabilities of another entity, even if such entities are affiliated with one another. Another potential benefit is the ability to create multiple pools of assets to transfer to different classes of heirs (the operating businesses to the active heirs, the leased real estate and/or equipment to the inactive heirs).

IV. Succession to Family Members

A. Transfer Tax Reduction Strategies. Most strategies relating to business successions to family members revolve around estate and gift tax reduction or payment techniques, transferring the business to the next generation at the cheapest transfer tax burden. Many of these strategies are discussed briefly below.

B. Entity Discounting. Subject to regulatory change becoming effective (see caution below), family transfers of business interests generally qualify for transfer tax discounting, as the interests in the entity themselves carry possible valuation discounts due to, among other things, lack of control (minority interest discount) and lack of marketability. While corporate stock can certainly lead to transfer tax discounting, such discounts may be more effective through limited liability company and/or family limited partnership structuring. Caution: Recently proposed regulations to IRC §2704, when and if finalized in their current or similar content, will significantly reduce, if not eliminate, transfer tax discounting in most common intra-family transfer situations.

C. Private Annuities. A sale of the company to the younger generation for a lifetime annuity (private annuity) can be done when the senior generational owners wish to receive ongoing cash flow, but desire to remove the appreciation of the business and, possibly, part of the current value of the business from the taxable estate. Note: To achieve the desired transfer tax purposes, the transaction must be, among other things, structured consistent with certain IRS mortality based tables.

D. Self-Canceling Installment Sales.Where, in addition to the objectives desired in the private annuity strategy, the senior generational owners wish to secure the future payment obligation of the junior generation members through a security agreement, deed of trust or some other provision of collateral arrangement, an installment sale of the business may be used instead, often with a self-canceling provision upon a certain event such as the death of the transferor owner. Note: To achieve the desired transfer tax purposes, the transaction must be, among other things, structured consistent with certain IRS mortality based tables.

E. Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts (GRATs). A transfer of a partial interest (or, a series of partial interests in the case of multiple short-term GRATs) can be accomplished through transfers to one or more grantor retained annuity trusts (“GRATs”). If properly structured and depending on the performance of the assets held in the trust (in this case, ownership interests in the business), the senior generational owners can transfer the remainder interest in the trust to junior generational owners free of transfer tax. Note: To achieve the desired transfer tax purposes, the transaction must be structured to, among other things, outperform IRS rates of investment return.

F. Intentionally Defective Grantor Trusts (IDGTs). An IDGT is an irrevocable trust that is “defective” for income tax purposes, but is effective for transfer tax purposes. A transfer of cash to an IDGT, followed by a sale of the business to the IDGT at fair market value, can, if done properly, transfer the appreciation of the business to the junior generational owners for estate tax purposes. Note: To achieve the desired transfer tax purposes, the transaction must be structured to meet various requirements under tax law.

G. Gift Giving Program. A gift giving program of annual exclusion gifts, gifts that use up the transfer tax exemption amount and/or even taxable gifts can remove the value of appreciating business interests from the taxable estate.

H. Life Insurance to Pay Estate Taxes. Life insurance can be obtained to provide funds to pay estate taxes, as well as to, among other things, replace the future earnings potential of the deceased or to build wealth for transfer to future generations. If structured properly (particularly taking note of the complexities caused by the application of Texas community property laws in cases where the surviving spouse of the insured is also intended to be a beneficiary), life insurance can be purchased through a trust in a manner whereby the life insurance proceeds are not included in the taxable estates of either the deceased or the surviving spouse.

I. 15 Year Payout of Estate Taxes. IRC §6166 generally provides that if a family owned business comprises more than 35% of the taxable estate, the estate may pay the estate tax owed on the value of the business in installments at a favorable interest rate over a period of 15 years if certain technical and procedural requirements are met. At least one recent judicial decision has ruled that the IRS has abused its discretion in automatically requiring a bond or a lien to secure the estate’s performance on the installment obligation.

J. Certain Stock Redemptions Not Treated As Dividend. IRC §303 generally provides that if a family owned business structured as a C corporation comprises more than 35% of the taxable estate, the proceeds received from the corporation redeeming the shares will be treated as a nontaxable sale to the extent of the estate tax and not as the receipt of ordinary income dividends if certain technical requirements are met.

V. Sale to Other Owners or Employees

A. Buy-Sell Agreements. A contract amongst the owners of a closely held business, often called a buy-sell agreement, can provide for the buyout of a withdrawing owner’s interest in the business.

1. Ascertain Purpose of Agreement. The owner of an interest in a closely held business has, with a small group of co-owners, built a business in which he or she has typically invested a great deal of personal wealth and his or her family’s future economic well-being. Accordingly, it is important that the owner ultimately receive value for his or her interest in the business if a withdrawal event occurs, which is far from automatic since no public market exists for most interests in privately held companies. Thus, one purpose of a buy-sell agreement might be to provide a buyout of an owner’s interest in the business that will economically benefit the withdrawing owner and/or his surviving family members (called “Purpose One” herein).

Additionally, in the event of a withdrawal of any one of the co-owners, the continuing owners may not wish to work with either a stranger to the business or with their former associate’s previously uninvolved surviving spouse or other family members. In such case, the business or the continuing owners will wish to acquire the interest of the withdrawing owner in a manner that does not create a hardship on the business or on the continuing owners or an undue drain on the cash flow of the business or of the continuing owners that would make the continuation of the business economically unattractive. Thus, a second purpose of a buy-sell agreement might be to provide a buyout of an owner’s interest in the business under attractive terms for the business or the continuing owners in order to assist in the continuation of the business for the continuing owners, their families and its employees (called “Purpose Two” herein).

2. Purchaser of the Interest. Generally, either the business will purchase the withdrawing owner’s interest (an “entity” agreement) or the continuing owners will purchase the withdrawing owner’s interest (a “cross-purchase” agreement). While there are several considerations, many practitioners prefer the cross-purchase structure so that the continuing owners may receive the benefit of an income tax basis in the purchased interest, which is lost if the entity purchases the interest. This author generally drafts such an agreement to provide that the entity have the first option to purchase and then the continuing owners, so that the decision can be postponed until the triggering event.

3. Mandatory or Option. A determination needs to be made as to whether the purchase of a withdrawing owner’s interest is mandatory or an option. Often, it is provided that some triggering events result in mandatory obligations to purchase, while other triggering events only create an option to purchase in favor of the business or the continuing owners.

4. Value of Interest. Some common methods of determining the purchase price of the withdrawing owner’s interest in the business: (i) by appraisal, (ii) by formula or (iii) by agreed upon value updated periodically.

a. “Purpose One”. If the primary purpose of the buy-sell agreement is to create a valuable “exit” for a withdrawing owner or his or her family (“Purpose One”), then special care should be taken that the designated method for determining the value of the interest creates an appropriate high fair market value for the interest. A fair market appraisal or a formula that is an appropriate multiple of earnings may be desirable. To protect the continued viability of the business, the purchase price can be paid over time and/or restrictions on the amount of each periodic payment can be provided for to ensure that the business will have adequate cash flow to meet its other obligations. The buy-sell agreement should generally provide for a mandatory obligation to purchase the withdrawing owner’s interest for all or most triggering events.

b. Life Insurance. Caution: If the triggering event is the death of the owner and the purchase price is to be paid from the proceeds of life insurance paid for directly or indirectly by the business, consider whether the surviving family members have ultimately received any additional payments for the purchased business interest. In such event, it is often the case that the deceased owner may have indirectly paid, or substantially paid, for the premiums on the life insurance through his or her pro rata interest in the business and, thus, could have received the benefit of the same life insurance proceeds outside of the buy-sell arrangement. That is, the deceased owner could have directly purchased the same life insurance coverage with the same equivalent, or substantially equivalent, money. His family would have then received the same death benefit from the life insurance policy, but would still possess the deceased owner’s interest in the business, having some value.

Suggestion: Purchase the same life insurance outside of and unrelated to the business and provide for the buy-out of the business interest out of future earnings of the business. If necessary, protections for the continuing owners could be provided for, such as, among other things, reducing the purchase price of the business interest, allowing a long-term payout of the purchase price and/or placing restrictions on the amounts of the purchase price installments.

c. “Purpose Two”. If the primary purpose of the buy-sell agreement is to facilitate the continuing owner’s acquisition of the withdrawing owner’s business interest (“Purpose Two”), then generally a designated method for determining the value of the interest that creates an appropriate low fair market value for the interest (such as “net book value”) may be selected. The buy-sell agreement should generally provide that the purchase is not mandatory, but an option in favor of the business or the continuing owners, for all or most triggering events. A mandatory requirement if the triggering event is death is often provided, with the purchase price being funded by life insurance proceeds. This works out well for the business and the continuing owners, as the buyout is funded through life insurance, the premiums for which have been, in many cases, substantially paid for indirectly through the deceased owner’s pro rata share of business funds.

B. Employee Agreement to Purchase. Many business owners, not having a suitable family member to act as successor to the business, may look to non-owner key employees of the business to purchase the business at the business owner’s retirement or death.

1. Long-Range Agreements. While it may be admirable to attempt to set these arrangements up even years in advance of a possible triggering event, there may be special problems involved in establishing these long-range arrangements. Circumstances may have changed between when the agreement was executed and the time of a triggering event, resulting in an unfair agreement for one side or the other or the need for a second negotiation session after the occurrence of the succession event. Even if circumstances have not changed and particularly if the triggering event is the death of the owner so that the threat of competition has been removed or diminished, the buying employee(s) may determine that they can simply capture and take the business elsewhere in an attempt to avoid paying the owner’s survivors the already agreed upon purchase price. Reliance upon even a binding agreement with strong covenants not to compete may be problematical at the time, as the pursuit of a potentially expensive and long-drawn out lawsuit by the deceased owner’s estate or survivors against presumably non-wealthy ex-employee defendants may not be a favorable situation to be in. In such case, the buying employee(s) may have significant leverage to pursue a second negotiation session with the deceased owner’s survivors.

2. Shorter-Term Agreements. An agreement with employees to purchase the business structured closer to an anticipated withdrawal event (such as within a year before the owner’s scheduled retirement) should work well and should be similar to the purchase of the business by outside third parties (discussed below). However, agreements with employees are usually seller financed and entered into with parties (the buying employees) with insubstantial assets. Accordingly, the arrangement should be carefully crafted with the view that the payment of the purchase price will be generated from future cash flow of the business.

3. Practice Continuation Agreements. Often various professional associations provide for a network of fellow professionals who can absorb the practice of a professional who has unexpectedly passed away. Somewhat standardized practice continuation agreements can then be entered into which generally provide for some form of continued payments to the surviving spouse for a certain term of years, usually determined as a percentage of the payments collected from future work on clients successfully transitioned to the purchasing practitioner. Of course, similar (or different) practice continuation agreements can be entered into independent of the resources of the applicable professional associations.

4. ESOPs. An owner’s stock in a corporation can be sold to the employees through an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). Although the creation and administrative costs are relatively high, an ESOP could be an attractive “exit” for the current owner and allows the employees to indirectly acquire the corporation through the use of pretax dollars because, within limits, the purchase payments for the owner’s stock are tax deductible.

VI. Sale to Outside Third Parties

A. Buyer’s Market. Due to long-standing market conditions and complications involved in obtaining third-party financing, the business acquisition arena continues to be generally a buyer’s market. Accordingly, generally speaking, the buyer with financial resources enjoys substantially increased leverage in structuring the acquisition and the contents of the legal instruments documenting the transaction. In that type of market, the buyer is often able to successfully negotiate one or more basic business points such as a relatively favorable purchase price, low down payment, substantial deferred payments of the purchase price which are seller financed, and no personal guarantee of the deferred payments of the purchase price. Oftentimes, deferred payments of the purchase price are based on contingencies, the most common of which are based on future productivity of the purchased business, sometimes referred to as an “earnout” contingency. In addition, payments that would otherwise be upfront payments of the purchase price are also deferred, in the form of withheld reserves or escrows, to secure various seller representations or to ensure that certain transferred net working capital thresholds are met. The content and wording of seller warranties and representations, and the related seller indemnification provisions, have been generally molded from decades of sophisticated crafting by large law firm representation of deal-advantaged buyers, providing increased buyer protection and the potential for purchase price clawback.

B. Negotiation Process. In a typical acquisition involving an attorney, the buyer will generally perform an extensive due diligence review of the company to be purchased and have prepared significant legal documents, usually in the form of an asset purchase agreement, stock purchase agreement or a merger or conversion agreement, along with numerous exhibits and related agreements, such as covenants not to compete, promissory notes, security agreements, consulting or employment agreements, and various due diligence and closing certificates of representatives of both buyer and seller. Of particular significance is also the inclusion, as exhibits, of often voluminous disclosure schedules to support copious seller warranties and representations contained in the agreement.

The due diligence and document preparation process not only entails a significant expenditure of both the buyer’s and seller’s time, emotion and energy, but also, the incurrence of significant expenses in the form of professional fees and related expenses. It is, therefore, imperative that both parties ascertain that there is a “real deal” at the earliest stage possible, so that a party to the transaction is not placed in the position of making unnecessary concessions in order to avoid losing its considerable investment in terms of time and money, which is growing more and more significant as the acquisition process continues.

Worst yet is the exposure of losing the entire deal at the tail end of the due diligence process, due to the inability of the parties to reach agreement on some material point, which point could have been resolved prior to the expenditure of substantial time and money in the acquisition process.

C. Certain U.S. Income Tax Considerations

1. From Seller’s Perspective. It is generally advantageous for the seller to obtain two U.S. income tax objectives when selling his business: (i) incur a single level of tax at (ii) individual capital gain rates.

One way to achieve these two objectives is for the seller to sell his equity interests in the entity conducting the business rather than the assets of the business themselves. However, in most scenarios, a buyer will not be willing to accept the risk of unknown or undisclosed liabilities that would carry over to the buyer in an equity interest purchase, in addition to buyer’s unwillingness to purchase equity interests due to the different tax objectives of buyer discussed below. Therefore, a seller is often not able to successfully negotiate an equity interest sale.

Other than depreciation recapture (including amounts previously expensed under IRC §179) taxed at ordinary income rates, a seller can generally achieve these two objectives even when selling the business assets, rather than the equity interests, for businesses conducted by “pass-through” entities, such as partnerships, limited liabilities companies and S corporations. In such cases, the U.S. income tax objectives of both seller and buyer can generally be accomplished through an asset sale and purchase.

When selling a business conducted by a C corporation, with its inherent double U.S. income tax structure, consideration of the concept of “personal goodwill” discussed below may ameliorate the harsh U.S. income tax consequences to seller under the right circumstances.

2. From Buyer’s Perspective. It is generally advantageous for the buyer to purchase assets rather than equity interests in order to allocate the purchase price to depreciable or amortizable assets for subsequent U.S. income tax benefits.

This generally works out fine for both buyer and seller when the selling entity is a “pass-through” entity, such as partnerships, limited liability companies and S corporations, where the assets of the entity can be purchased without creating a double tax situation for the seller and, at the same time, allowing for allocation of the purchase price among depreciable or amortizable assets for future cost recovery deductions which will benefit the buyer.

When purchasing a business conducted through a C corporation, with its inherent double U.S. income tax structure, consideration of the concept of “personal goodwill” discussed below may ameliorate the harsh U.S. income tax consequences to seller and still allow future tax benefits to the buyer through future amortization deductions of goodwill intangibles.

3. Personal Goodwill. As many purchasers of corporate businesses are insistent on purchasing the assets of the business rather than the stock in the corporation, a double taxation situation occurs for the shareholders of a selling C corporation, a tax at the corporate level (without benefit of a lower capital gain tax rate) and another tax at the shareholder level.

A concept designed to, among other things, eliminate a substantial portion of the double taxation under the right circumstances is to recognize that a large portion of the “goodwill” value of a C corporation is not really goodwill of the corporation, but rather goodwill of the key employee/owner (“personal goodwill”). Accordingly, in the right situation, a large part of the purchase price could be allocated and paid directly to the key employee/owner and treated as the sale of a capital asset, resulting in one level of tax at individual capital gain tax rates. There are two seminal key cases in this area: (i) Martin Ice Cream Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 110 T.C. 189 (1998) (“Martin Ice Cream”) and (ii) William Norwalk, Transferee, et al v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, T.C. Memo 1998-279 (“Norwalk”).

In Martin Ice Cream, the Tax Court held that there is no saleable goodwill in a corporation where the business of the corporation depends on its key employees, unless the key employees had entered into a covenant not to compete with the corporation or another agreement whereby their personal relationships with clients become the property of the corporation. In Norwalk, the court held that the shareholder accountants in a liquidating accounting firm realized no taxable income for receipt of corporate goodwill, the goodwill already residing in the individual shareholder accountants absent any covenant not to compete or similar agreement with the accounting firm. But also see two later contra cases: Larry E. Howard v. U.S., Doc 2010-17126 (E.D. Wash. 2010), personal goodwill not allowed where dentist was subject to a pre-existing covenant not to compete agreement with his wholly owned practice, and James P. Kennedy v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2010-206, personal goodwill payments treated as payments for services where seller worked for buyer for several years after sale of company.

Also to be considered is the principle that the presence of personal goodwill is presumably determined in a competitive context, not in a retirement context. That is, it appears that the issue is not whether the corporation could continue if the shareholder were to retire and not be active in the same line of business, but rather, it appears that the question is whether the corporation’s business would follow the shareholder if the shareholder engaged in a competitive business.

The percentage of potential dollars of U.S. income tax saved from re-allocating each dollar away from corporate goodwill to personal goodwill is 29.7%, assuming a corporate tax rate of 34%, an individual capital gain tax rate of 20%, and non-application of the 3.8% Medicare surtax on the sale of personal goodwill (gain on sale of trade or business property exception), computed as follows:

| Scenario One: Sale of Assets, No Personal Goodwill | |

| Sales Proceeds | $1.00 |

| Corporate Tax (34%) | (0.34) |

| Remaining Funds Distributed to Shareholder | 0.66 |

| Individual Dividend Tax (20%) | (0.132) |

| Individual 3.8% Tax on Net Investment Income | (0.025) |

| Remaining Funds for Shareholder After U.S. Income Taxes | $0.503 |

| Scenario Two: Sale of Assets, With Personal Goodwill | |

| Sales Proceeds (Paid to Shareholder for Personal Goodwill) | $1.00 |

| Individual Capital Gain Tax (20%) | (0.20) |

| Remaining Funds for Shareholder After U.S. Income Taxes | $0.80 |

| Difference: $0.80 – $0.503 = $0.297 or 29.7% |

4. IRC §1060. IRC §1060 was enacted primarily to address certain problems encountered by the IRS with respect to the prevalent practice of inconsistent tax reporting by buyers and sellers of the tax consequences relating to their business sales and purchases. Sellers would tend to allocate the purchase price toward goodwill to obtain favorable capital gain rates and buyers would allocate the same amounts to depreciable tangible personal property to obtain depreciation deductions. IRC §1060 requires the buyer and the seller to allocate the purchase price amongst the purchased assets pursuant to the residual method of accounting. To help inform the IRS of such allocation, both buyer and seller are required to file IRS Form 8594 with their respective U.S. income tax returns in the year of sale in order to report such allocation. If the buyer and seller agree to a purchase price allocation in the acquisition documents, then the parties are required to report the U.S. income tax consequences of such sale consistent with such agreement.

D. Letter of Intent

1. In General. Although negotiation of some points in the later stage of the transaction is almost always unavoidable, the preparation of the definitive agreements should be made as anti-climatic, as possible. The most significant negotiation stage of the business acquisition should be consummated at the beginning of the negotiation process and is best documented through a preliminary document often referred to as a letter of intent. Oftentimes, not enough attention is placed on this important document, so that some potentially contentious issues are left for resolution later on in the process; or, too often, it is omitted in its entirety.

2. From Buyer’s Perspective. The letter of intent should clearly outline all major business points, which could be “deal breakers”, including, aside from the obvious amount and payment terms of the purchase price, (i) whether any personal guarantees are to be required of the buyer; (ii) whether any assets of the purchased business or other assets of the buyer are to be used as collateral by the seller; (iii) the contents of warranties and representations and the consequences of any violation of any warranties and representations, including whether a right of offset will be granted; (iv) a long survival period for the seller’s warranties and representations after closing; (v) a high “ceiling” for which the indemnification obligation for breach of seller’s warranties and representations cannot exceed; (vi) whether legal opinions will be required; (vii) the establishment of contingencies on deferred payments, including the parameters of any “earnout” provision; and (viii) restrictions on seller conduct pending the closing process.

3. From Seller’s Perspective. Aside from the obvious amount and payment terms of the purchase price, the seller will want (i) personal guarantees of solvent individuals or entities associated with the buyer for any deferred payments; (ii) a security interest in some or all of the purchased assets of the business or in other collateral of the buyer to secure payment of any deferred payments; (iii) specific and short term dates for each step of the closing process, with required earnest money deposits at each stage; (iv) confidentiality provisions; (v) provision for a “deal-breakup” fee; (vi) specific delineation of employment or consulting agreement terms; (vii) provision for “reduced” warranties and representations of seller; (viii) a high “basket” amount before indemnification for breach of seller’s warranties and representations would apply; (ix) a low “ceiling” for which the indemnification obligation for breach of seller’s warranties and representations cannot exceed; (x) a short survival period for the seller’s warranties and representations after closing; and (xi) removal or restriction of contingencies on deferred payments.

E. The Due Diligence Process

1. Seller’s Provision of Information. As a buyer often has the ability to choose among alternative businesses to purchase, for a seller to achieve the highest sales price, most favorable terms and a quick closing, the seller must be prepared to provide pertinent information regarding the business in a highly organized and expedient fashion. In the case of financial information about the business, the seller should be aware that information reported to various taxing authorities, such as federal income tax returns, federal payroll tax returns and state sales tax returns generally will be more credible than internally generated financial statements and reports. Other third party information, such as bank statements, will also be considered highly credible as evidencing actual income and expenses. Therefore, inconsistencies among such data should be reviewed and handled prior to dissemination of information to the buyer. As entries in the financials involving activities between the seller and it owners (such as advances to and from the owners) can lead to various issues in the sales process, related party entries should be “cleaned up” and/or removed from the books in connection with the initial analysis of the seller’s financial information. Audited or compiled financial statements by a reputable CPA firm should provide additional credibility, as well.

2. Early Initiation of Third Party Actions and Consents. Oftentimes, actions or consents of third parties may be required to properly accomplish the transfer of the business from the seller to the buyer. Early initiation of obtaining such third party actions or consents is imperative with respect to a timely closing. Third party action and/or consent is often involved where there are third party liens that need to be released, real estate leases to be assumed and customer/vendor/franchisor/licensor agreements to be assigned. Curing title to assets may be involved, as well, particularly for real estate, personalty subject to a security interest and intellectual property rights. Be sure to order early a title policy commitment for all real estate to be purchased and a UCC search on each selling party. All environmental studies, structural inspections and heavy equipment testing should be accomplished early, as well.

3. Quick Closing Desired by Seller. Particularly, the seller should desire as short a due diligence and document preparation period, as possible. As the time period before closing lingers on, there is more opportunity for a buyer to find a better deal. Furthermore, because knowledge of an impending sale generally spreads quickly to employees, suppliers and customers (often with detrimental effect), a long pre-closing period may have a chilling effect, not only with respect to the current buyer, but with future buyers, as well, in the event the current purchase falls through. Substantial earnest money, with specific time commitments for future actions, should be sought by seller, particularly in view of the fact that a newly formed corporate shell will often be the party executing any binding agreement involving the acquisition as buyer.

F. Definitive Agreements

1. Warranties and Representations. The seller naturally desires to receive the purchase price from the sale of the business with very limited rights of the buyer to obtain a refund back of all or a portion of the purchase price or to reduce or eliminate deferred payments. In addition to certain contingencies which may be placed on deferred payments, a buyer usually obtains warranties and representations from the seller, which if breached and causing damage to buyer, give the buyer certain rights against the seller.

Attorneys for sellers typically attempt to restrict the warranties and representations to the basic ones regarding organization and existence, ownership of stock or assets, authority, no violation and no default.

Buyer’s counsel usually requires a myriad of additional warranties and representations, including accuracy of financial statements, absence of certain changes, tax matters, contracts and agreements, absence of liens, fringe benefits, pension and other retirement plans (ERISA matters), real estate, leases, insurance, intellectual property, permits, personnel data, labor relations, compliance with laws, inventory, transactions with related parties, environmental compliance, accounts receivable, accounts payable, customers and suppliers, improper payments, warranty claims, interests in customers and vendors, litigation, and full disclosure. Particularly for larger transactions, the seller’s attorney may be required to render a legal opinion as to the validity of certain warranties and representations.

As a seller will often be a shell entity after the sale of the business and distribution of the sales proceeds to its owners, it is important from the buyer’s perspective to have the ultimate recipients of the sales proceeds, usually the owners or shareholders, join in on the warranties and representations and assume joint and several liability with respect to breaches thereof.

2. Some Specific Purchase Agreement Provisions. Most modern purchase agreements will contain substantial and sophisticated seller warranties and representations provisions, related seller indemnification provisions and other terms and conditions that may need special consideration. This is true, more and more, even for relatively small deals due to the easy accessibility of modern day mergers and acquisitions form agreements. Various alternatives to some of these provisions are discussed below.

(a) Material Adverse Effect. The definition of “Material Adverse Effect”, a key term in many of the warranties and representations provisions, can be defined to, among other things, (i) include, exclude or be silent on adverse effects relating to seller’s prospects, (ii) include, exclude or be silent with respect to forward-looking language (such as, “or could reasonably be expected to have a materially adverse effect”), (iii) include, exclude or be silent with respect to possible carveouts that would not be considered as causing a material adverse effect (decline in general market conditions, decline in industry market conditions, decline due to acts of war, decline due to changes in law, decline due to changes in GAAP or other applicable accounting principles, decline due to announcement of the transaction, etc.), and/or (iv) if such carveouts are included, include or exclude the inapplicability of the carveout if seller is disproportionately affected.

(b) Materiality Scrape. Sophisticated buyers often include a “materiality scrape” in the indemnification provisions of the modern purchase agreement. Although the specific warranty or representation contains a materiality qualification, the materiality qualification is disregarded (it is “scraped”) when calculating damages for an indemnification claim against seller. Example language: For purposes of determining the failure of any representations or warranties to be true and correct, the breach of any covenants or agreements, and calculating Losses hereunder, any materiality or Material Adverse Effect qualifications in the representations, warranties, covenants and agreements shall be disregarded.

(c) Knowledge of Seller. The definition of “knowledge”, another key term in many of the warranties and representations provisions, can be defined to, among other things, (i) include only actual knowledge, (ii) include also constructive knowledge (knowledge that could have been obtained after reasonable or due inquiry), (iii) include the knowledge of some or all owner/members only, and/or (iv) include the knowledge of non-owner/member officers, key managers and department heads, or all employee personnel and agents.

(d) Knowledge Scrape. Sophisticated buyers often include a “knowledge scrape” in the indemnification provisions of the modern purchase agreement. Similar to the “materiality scrape” discussed above, and although the specific warranty or representation contains a knowledge qualification, the knowledge qualification is disregarded (it is “scraped”) when calculating damages for an indemnification claim against seller.

(e) Accounting Standard. The accounting standard for the warranties and representations regarding fair presentation of seller’s financials, whether GAAP, modified GAAP, the accounting principles consistently applied by seller on a historical basis, or some other appropriate standard approved by the parties, should be carefully considered.

(f) Undisclosed Liabilities. Seller will generally indemnify buyer for undisclosed liabilities. However, consider whether it is appropriate to word the warranty to favor the buyer, by defining an undisclosed liability in terms of liabilities not reflected or reserved against on the applicable balance sheet.

(g) Qualified to Do Business in Other Jurisdictions. Buyer will usually include a representation that seller has complied with all qualification laws in all jurisdictions seller does business in. Becoming compliant in such jurisdictions often requires several years of back taxes to be paid, in addition to the relatively modest registration fees. This is often an area of non-compliance by small sellers that should be thought about carefully by seller before agreeing to such a representation.

(h) Compliance with Laws. A standard representation of the seller will be that seller has operated the business in compliance with all laws. While it is usually intended that the seller will indemnify the buyer for all liabilities that relate to the seller’s conduct of the business before the date of closing, it should be considered whether this warranty extends seller’s indemnification for liabilities related to the buyer’s conduct of the business after the date of closing, if the buyer were to continue operations the same way that the seller did if such operations were in violation of applicable law (such as, for example, a continuation of business operations that are not in compliance with OSHA requirements).

(i) Full Disclosure Representations. Buyers will often include a “global” representation that seller has provided all information that might have a materially adverse impact on seller’s business that has not been disclosed in the agreement. Sellers will usually want a provision that the buyer may only rely on the specific information warranted.

(j) Due Diligence Materials Warranted. Buyers will often include that the accuracy of all materials and information submitted to the buyer at any time are warranted. This would include the vast due diligence materials (often including forward-looking projections or assumptions) submitted to buyer prior to execution of the final agreement and which often are not included in the disclosure schedules attached to the agreement. Sellers will generally want only the specific information disclosed in, and attached to, the final agreement to comprise seller’s warranted disclosures and seek to have such a provision excluded from the final agreement.

(k) Non-Reliance Provisions. Buyer will usually not include any warranty disclaimer language in the agreement. Seller should consider including a provision that seller is making no other representations or warranties, express or implied, not specifically made in the agreement and that buyer agrees that it is not relying on any warranties or representations in consummating the acquisition, except for the warranties and representations specifically made in the agreement.

(l) Sandbagging Provision. Buyer may include a provision that buyer’s prior knowledge of a breach of a representation or warranty does not affect seller’s indemnity obligation with respect to such representation or warranty. In other words, there is no relevance as to whether buyer was relying on such representation or warranty in consummating the transaction. Sellers would generally prefer an anti-sandbagging provision (buyer’s pre-closing knowledge of the breach eliminates liability for the breach).

(m) Diminutions in Value as Measure of Damages. In its laundry list of types of damages that are recoverable against seller in seller’s indemnification provisions, buyers often include “diminutions in value”. Particularly where the purchase price has been determined as a multiple of earnings or where the post-sale value of a company is determined as a multiple of earnings, this type of language could lead to damages amounting to multiples of the actual dollar amount involved. Sellers would generally prefer to omit such a measure of damages or expressly exclude it.

(n) Consequential, Indirect and Special Damages as Measure of Damages. In its laundry list of types of damages that are recoverable against seller in seller’s indemnification provisions, buyers often include “consequential”, “indirect” and/or “special” damages, which substantiality increases the seller’s potential indemnification liability. Sellers would generally prefer to omit such terms in the definition of included damages or expressly exclude them from recoverable damages.

(o) Survival Periods. In the normal setting involving sophisticated parties, it is difficult for a seller to avoid extensive warranties and representations, often involving a “right of offset”. However, important limitations on such warranties and representations often are not difficult to achieve. Since the extensive warranties and representations (and right of offset) usually result from the buyer’s fears that its due diligence efforts cannot pick up every material defect, and that only a period of operation can make such defects discernible, the seller can often successfully obtain a removal or lapse of all or most warranties and representations after a reasonable period of time of buyer’s operation of the purchased business (for example, twelve to eighteen months from closing). Longer or indefinite periods will still be pursued by knowledgeable buyers for fundamental representations and/or fraud.

(p) Tiered Survival Periods/Carveouts. In exchange for a relatively short survival period, buyers will often seek to create tiers of survival periods. The short survival period would apply generally to all warranties and representations, but certain specified carveouts, sometimes call “fundamental representations”, will be assigned an extended or indefinite survival period. Sellers will generally attempt to restrict or limit the number and applicability of such warranties and representations, as well as the length of the survival period(s).

(q) Survival Period Carveouts/Fraud. Buyers will often have a carveout relating to fraud which would have a long or indefinite survival period. However, the fraud carveout is usually worded to include similar, but importantly distinctive, concepts such as “intentional misrepresentation”. Sellers will generally seek to eliminate any concepts not specifically worded as fraud, in order to preserve all of the “badges of fraud” as necessary elements of proof, including the element of detrimental reliance.

(r) Ceilings. Usually the aggregate amount of damages that can be recoverable against the seller can be limited to a specified dollar amount, referred to as the “ceiling”. Buyers will usually include a provision setting a high ceiling such as the total purchase price amount. Sellers will seek a much lower ceiling such as 10% to 25% of the total purchase price. Buyers agreeing to a lower ceiling amount may then seek tiered ceilings, providing, for example, a higher ceiling or no ceiling for damages caused by fraud or breach of a fundamental representation.

(s) Baskets. In order to avoid a “nickel and dime” approach to seller indemnification claims, a base amount, called a “basket”, is usually established, so that no damages may be awarded to buyer until the basket amount has been achieved. Baskets are often either “deductible baskets” (seller is not responsible for the basket amount, only the excess) or “tipping baskets” (once the basket amount is achieved, seller is also responsible for the basket amount). Buyers will generally seek low tipping basket amounts (for example, a dollar amount with no relationship to the size of the deal), while sellers will generally seek a high deductible basket amount (for example, an amount approximating 0.5% to 1% of the total purchase price). Buyers also often seek a provision that eliminates baskets if the claims relate to fraud or breach of a fundamental representation.

(t) Responsibility for Sales Tax on Sale of the Business. Buyers generally include a provision that the seller is responsible for any sales or other transfer tax due on the sale of the business or its related assets. Sellers in Texas often rely on the occasional sale exemption (TAC §3.316) that no sales tax is due in Texas; however, careful consideration of such exemption should be made as the exemption is not automatic and has some qualifications.

(u) Seller’s Cost of Representation as Leakage. Particularly in the case of a small closely held company, the owners of which having relatively little liquid financial resources outside of the company, the owners of seller may be placed in a position where they must make concessions because they cannot afford the costs of representation. This is because buyers often require that the costs of representation be funded by the owners directly and not from funds of the seller. If funded by the seller, then often the modern purchase agreement provides that (i) buyer has the right to terminate the agreement prior to closing, as such use of funds would be in violation of the restrictions on the use of seller’s assets pending closing, (ii) such use of seller funds constitutes “leakage”, which reduces the purchase price dollar for dollar and/or (iii) such use of funds impacts the net working capital reserve, if the deal has one, which potentially reduces the purchase price dollar for dollar. Sellers, recognizing that transaction costs might be significant and may need to be paid pre-closing, may wish to provide that costs of representation and other transaction costs may be paid directly by seller. Sellers may also provide that the purchase price and/or net working capital thresholds be adjusted to recognize that there will be transaction costs that, in seller’s mind, should not reduce the purchase price.

(v) Confidentiality Provisions. Prior to the preparation and execution of the definitive purchase agreement, the parties have usually entered into a comprehensive confidentiality and nondisclosure agreement that primarily protects the seller’s information in the event the sale is not consummated. The modern purchase agreement also usually contains a confidentiality provision, but it is primarily worded to protect the buyer after the sale is consummated. It often also provides that the confidentiality provisions are terminated if no closing takes place. It would also be standard for the purchase agreement to contain an “entire agreement” provision. It might be prudent for a seller to make sure the “entire agreement” provision references the earlier confidentiality and nondisclosure agreement as an agreement that remains binding between the parties and does not terminate if the deal is not closed.

3. Escrows and Reserves. To further protect buyers and entice buyers to proceed with a business acquisition, certain purchase price payments that would otherwise constitute upfront cash down payments for the business will be carved out as an escrowed fund, or otherwise reserved as a holdback or deferred payment. Common escrows and reserves include: (i) cash escrows or reserves, (ii) working capital escrows or reserves, (iii) debt escrows and reserves, and (iv) indemnity escrows and reserves. Buyers will generally attempt to establish sizeable, long-lasting escrows and reserves and sellers will generally resist and attempt to limit or eliminate such reserves.

4. Other Closing Documents. Aside from the definitive basic agreement, usually in the form of an asset purchase agreement, a stock purchase agreement or a merger or conversion agreement, there are other numerous important legal documents associated with the business acquisition. There will be various documents relating to title of the purchased assets and the release or assumption of prior liens, such as bills of sale, warranty deeds, releases of liens and UCC-3 termination statements. In the case of a seller financed or leveraged buyout transaction, there will be various documents evidencing seller’s right to deferred payments, such as promissory notes, security agreements, deeds of trust, UCC-1 financing statements and/or guaranty agreements. In connection with leased assets, there may be lease agreements, estoppel certificates from existing landlords and assignments of leases, including landlord consents. For intellectual property rights, there may be patent assignments and license agreements to be obtained. Oftentimes, there are restrictive covenant agreements, providing for covenants not to compete and nonsolicitation prohibitions, as well as employment agreements and/or consulting agreements, whereby the seller, or individuals affiliated with the seller, continue to work for, and receive payments from, the buyer in the future.

G. Continuing Relationship. Due to the continuing existence of seller financing in many business acquisitions and the often continuing relationship between seller and buyer through employment and consulting agreements, it is important to recognize that often the relationship between buyer and seller does not end at closing, but rather, in a real sense, only begins. The structuring and documentation of all of the important aspects of this ongoing relationship is of vital importance. Throughout the negotiation process and the document preparation stage, the parties must always be cognizant and deal effectively with the ramifications that there will be, in most likelihood, a continuing relationship between the parties, oftentimes for an extended period of time after the transfer of the business from seller to buyer.

VII. Reactive Succession

Even if the need for succession comes totally unplanned and unexpectedly, then most or all of the alternatives discussed above may became doable or applicable, except that the time-frame for action has become compressed, possibly extremely compressed. Hopefully, one or more family members can step in and continue management and ownership of the business. If no family members are suitable for succession, retention of key employees through various mechanisms (employment contracts, phantom stock plans, stock options, etc.) may become even more important in order to avoid a distress sale of the business.

VIII. Conclusion

Substantial impediments (some internal, some external) stand in the way of an efficient transition of a closely held business to its successors. In fact, more often than not a family business does not successfully transfer to the next generation of owners. However, significant succession avenues do exist to enable a business owner to either pass the business on to his or her heirs or to sell the business to other parties in a much more effective manner than if no succession tools or planning are considered. With sufficient thought and implementation, a good succession plan can be developed for most any closely held business.